Introduction

To introduce the subject of the paper we begin with the illustrative example of \(k\)-coloring a random graph.

The random \(k\)-coloring problem is defined as follows:

Let \(G\) be a random graph with average degree \(d\). Is it possible to properly \(k\)-color the vertices of \(G\)?

Remark. Throughout the note we will use the “configuration model” of random graphs: namely, we randomly sample a graph from the set of all graphs with \(nd/2\) edges. However, morally this is quite similar to an Erd"os-Renyi graph with the same edge density.

The answer to this existential problem is, that there is a threshold at \(d=2k\ln k\).

Proposition. If \(d> (2+\varepsilon)k\ln k\) then the answer is almost certainly no [TODO: prove]. On the other hand, a second moment method calculation [TODO: do it] shows that if \(d<(2-\varepsilon)k\ln k\) then with probability \(1-o(1)\) [TODO: is the probability expo good?] \(G\) is \(k\)-colorable.

Proof. The proof of existence of a solution is non-constructive: we use the second moment method.

Proposition. If \(d<k\ln k\) then there is an efficient algorithm for \(k\)-coloring \(G\).

Proof. The algorithm is as follows:

while not all vertices are colored:

Let v be a vertex with the fewest remaining choices for its color

Assign v a random available color[TODO: prove that this works]

Let the algorithmic threshold denote the largest edge density where we have efficient algorithms for \(k\)-coloring. Let the existence threshold denote the largest edge density where we are guaranteed (with good probability) that a \(k\)-coloring exists. Note that there is a gap between the algorithmic threshold and the existence threshold. This is a quite general phenomenon across many CSPs; for instance it also occurs for \(k\)-SAT. Achiloptas and Coja-Oghlan’s goal in this paper is to provide an explanation of the gap between these thresholds. They do so by giving a description of the solution space geometry, and showing that this space undergoes a dramatic change when we cross the threshold below which we have efficient algorithms for \(k\)-coloring.

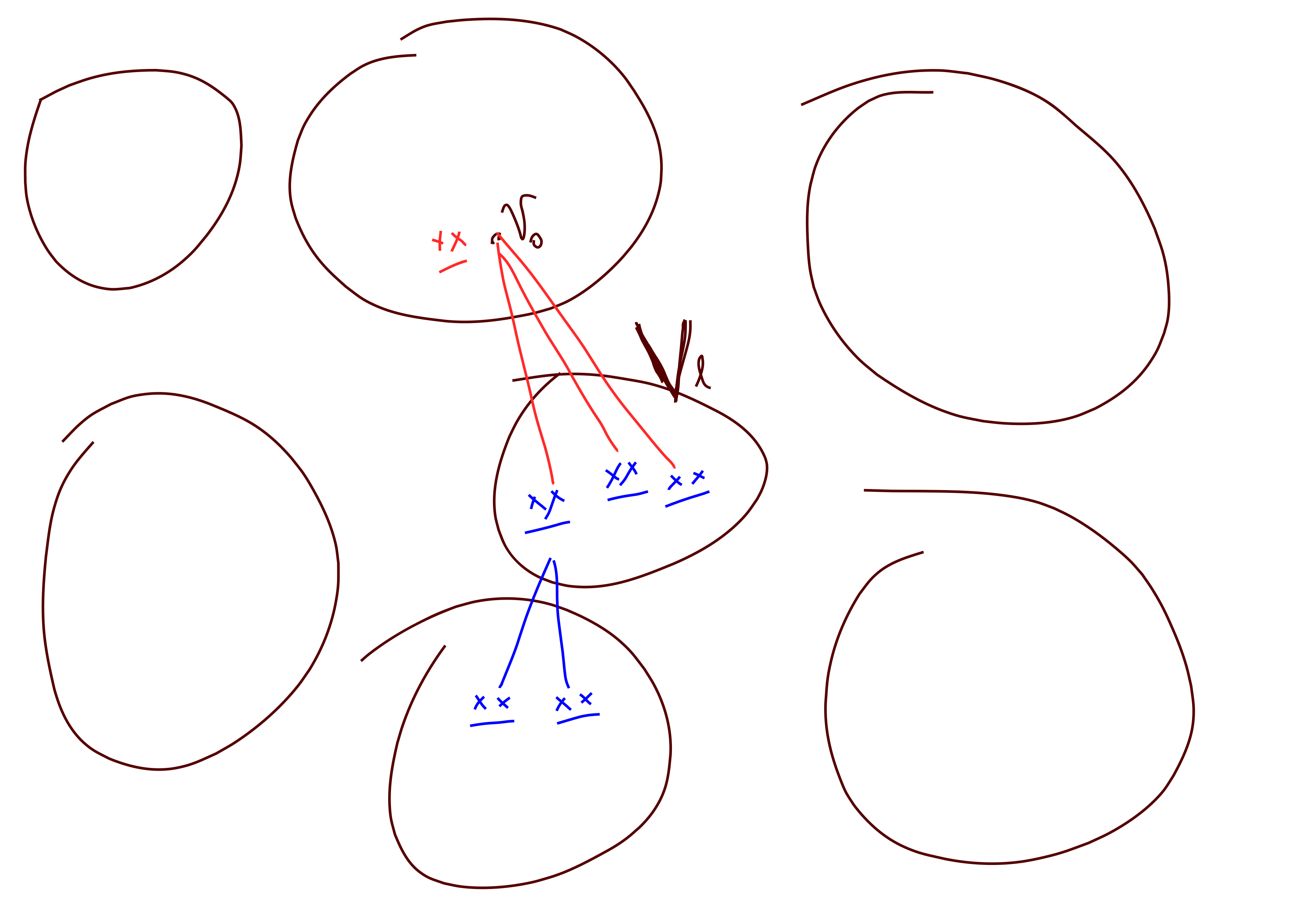

First we define what we mean by solution space geometry, and describe qualitatively the phase transition that occurs. The space of \(k\)-colorings is simply \([k]^{n}\). We can think of this as a “landscape”. The height in the landscape corresponds to the number of violated constraints (i.e., monochromatic edges). The height of a path between two colorings is the largest height at any coloring along the path. The distance between two colorings is the number of vertices that they assign different colors. Below the algorithmic threshold they show that there is a “giant ball” of solutions: this ball is large, and it is easy to move between solutions, in the sense that starting from a given solution there is a nearby solution that you can walk to along a low height path. In contrast, above the algorithmic threshold (but still below the existence threshold so that solutions exist) the solution space shatters and looks like an “error correcting code”. More specifically, the solution space transitions to consisting of an exponential number of regions, none of which are very large, and such that the regions are very far apart and separated by large heights (or “energy barriers”).

The most important idea in their analysis is a transfer principle. Roughly speaking this principle says that the view of the landscape from a random valley is basically the same as the view from a planted valley. In a planted instance of random \(k\)-coloring instead of uniformly randomly choosing a graph \(G\) of appropriate average degree, we first fix a coloring \(\sigma\in [k]^{n}\) and then select \(G\) from amongst graphs with the appropriate average degree which are properly colored by \(\sigma\). Intuitively, if a random coloring instance has a very large number of solutions on average then adding one more solution won’t change its landscape too much. However, reasoning about the planted model turns out to be much easier than reasoning about the uniform model.

Now we develop these notions more formally. For graph \(G\) and coloring \(\sigma\in [k]^{n}\) let \(H_G(\sigma)\) count the number of violated constraints (monochromatic edges) if we color \(G\) via \(\sigma\). Let \(S(G)\) denote the set of colorings \(\sigma\) with height \(H_G(\sigma) = 0\); that is, \(S(G)\) is the set of proper \(k\)-colorings of \(G\). Define the distance between two colorings to be the number of vertices which they assign different colors. A cluster of \(G\) is a connected component of \(S(G)\), where two colorings are considered adjacent if they have distance \(1\) (differ on a single vertex). A region is a non-empty union of clusters.

Then, the shattering phenomenon can be formalized as follows:Definition. There exists a partition of \(S(G)\) into regions such that:

- The number of regions is at most \(\exp(\beta n)\),

- The distance between distinct regions is at least \(\zeta n\),

- All paths between distinct regions have height at least \(\theta n\).

Theorem. Shattering happens right above the algorithm threshold for \(k\)-coloring.

Fix graph \(G\) and a proper \(k\)-coloring \(\sigma\) of \(G\). We say that a vertex \(v\) is \(f(n)\)-rigid (with respect to \(G,\sigma\)) if every coloring \(\tau\in S(G)\setminus \left\{ \sigma\right\}\) is distance at least \(f(n)\) away from \(\sigma\). Otherwise we say that vertex \(v\) is \(f(n)\)-loose. They show:

Theorem. Below the algorithm threshold all variables are loose (with good probability). Above the algorithm threshold most variables are rigid.

proof sketches

Now we present proof sketches for these theorems.

The most important part of the argument is the transfer principle, i.e., showing that we can understand the view from a random solution by looking at the view from a planted solution.

To get some intuition for the transfer principle it is useful to look at a simpler but morally similar case.Example. Let \(M\) be a binary matrix with \(r\) ones in each row and \(c\) ones in each column. Consider the following two distributions over ones in the matrix:

- Sample a random row and then choose a random one in that row.

- Sample a random column and then choose a random one in that column.

Clearly both of these methods for sampling produce the uniform distribution over ones in \(M\).

Now, suppose that we construct matrix \(M'\) as follows: Fix a number \(N\in \mathbb{N}\). Let \(\mathcal{X}\) denote the set of all \(k\)-colorings of vertex set \([n]\) where each color is used exactly \(n/k\) times. \(\mathcal{X}\) will index the rows of \(M'\). Let \(\mathcal{G}\) denote the set of all graphs \(G\) on \(nd\) vertices that can be properly \(k\)-colored in exactly \(N\) different ways by colorings \(\chi\in \mathcal{X}\). \(\mathcal{G}\) will index the columns of \(M'\). We put a one in entry \((\chi\in \mathcal{X}, G\in\mathcal{G})\) if \(\chi\) is a proper coloring of \(G\).

By symmetry, each row of \(M'\) has the same number of ones in it. By definition each graph \(G\in\mathcal{G}\) permits exactly \(N\) colorings \(\chi\in \mathcal{X}\). Thus, each column of \(M'\) also has the same number of ones in it.

Now, in the same manner as our earlier thought experiment we can define two equivalent ways of uniformly randomly sampling a \(1\) in the matrix.

- First choose a random graph \(G\in \mathcal{G}\) and then sample a random coloring \(\chi\) from among all \(\chi\in \mathcal{X}\) that properly color \(G\).

- First choose a random coloring \(\chi\in\mathcal{X}\) and then sample a random graph \(G\) from among all graphs \(G\in\mathcal{G}\) properly colored by \(\chi\).

The first option corresponds to considering the view from a random solution, while the second option corresponds to considering a view from a planted solution. In this situation the two distributions defined are identical.

However, this matrix \(M'\) is not the distribution we actually want to sample from. Rather we are interested in the following distribution:

Sample a random graph \(G\) with average degree \(d<(2-\varepsilon)k\ln k\). Then, sample a random proper coloring of \(G\) (assuming one exists, which it does with good probability).

This distribution over \(G,\chi\) pairs is quite complex however, and it would be more convenient to study the following distribution:

Choose a random coloring \(\chi\) and then choose a random graph \(G\) that is properly colored by \(\chi\).

Their transfer principle gives a very precise sense in which these distributions are similar.

Lemma. Let \(G_{n,m}\) be a random graph with \(n\) vertices and \(m\) edges and let \(S(G)\) denote the number of proper \(k\)-colorings of \(G\). Then, with high probability we have \[ \ln(|S(G_{n,m})|) - \ln \mathop{\mathrm{\mathbb{E}}}(S(G_{n,m})) < o(n). \]

Proof. [TODO: do stuff here]

The proof combines analysis of the second moment \(\mathop{\mathrm{\mathbb{E}}}[|S(G_{n,m})|^2]\) with theorems of Freidgut concerning sharp thresholds.

To state the transfer principle we must first formally define the distributions we are concerned with. First, define the uniform model \(U_{n,m}\) as follows:

Sample a random graph \(G\) with \(m\) edges, and then sample a random proper \(k\)-coloring \(\chi\) of \(G\) (assuming that one exists). Output \((G, \chi)\).

Now, define the planted model \(P_{n,m}\) as follows:

Then, the transfer theorem says:Generate a uniformly random \(k\)-partition \(\chi\in [k]^n\). Choose a uniformly random subset of \(m\) edges from amongst the edges that are not monochromatic under \(\chi\). Output \((G, \chi)\).

Theorem. Let \(d = 2m/n \le (2-\varepsilon)k\ln k\). There exists \(f(n)=o(n)\) such that the following is true. Let \(D\) be any graph property such that \(G_{n,m}\) has \(D\) with probability \(1-o(1)\) and let \(E\) be any property of pairs \(G,\chi\) where \(\chi\) properly colors \(G\). Suppose that \[ \Pr_{P_{n,m}}[(G, \sigma) \text{ has } E \mid G \text{ has } D]\ge 1-\exp(-f(n)). \] Then, \[ \Pr_{U_{n,m}}[(G,\sigma) \text{ has } E] \ge 1-o(1). \]

Proof. [TODO prove this]

The rough idea for the proof of this is that because we have really good concentration on the number of ones in the rows and columns of our matrix it’s basically just as good as having all rows and columns actually have the same num of ones.

In the remainder of the note we will show how to use the transfer principle to prove their results about loose/rigid variables and about shattering/non-shattering.

Loose Variables Below the Algorithm Threshold

In this section we show that below the algorithm threshold with good probability all variables are loose. Recall what this means: for any proper coloring \(\chi\) of our graph and any vertex \(i\in [n]\) we want to exhibit a “nearby” coloring \(\tau\) – nearby in the sense that we want \(\tau,\chi\) to assign different colors to at most \(o(n)\) vertices – with \(\tau(i)\neq \chi(i)\). To show this we give a simple algorithm that give \(\chi,i\) finds such a nearby coloring where \(i\)’s color is flipped.

The analysis of the algorithm will use notion of list chromatic number. We say that graph \(G\) is \(\eta\)-list-colorable if for any set of color lists \(C_1,\ldots, C_n \in \binom{[k]}{\eta}\) there exists a proper coloring \(\chi_1,\ldots, \chi_n\) of the vertices with \(\chi_i \in C_i\) for all \(i\). We remark that the list-chromatic number of a graph (the smallest \(\eta\) for which \(G\) is \(\eta\)-list-colorable) is at least as large, and possibly larger, than the chromatic number of \(G\).

Now we define the properties \(D,E\) which we will use in the transfer principle.

Let \(E\) be the property of \((G,\chi)\) that all vertices are \(o(n)\)-loose.

Let \(D\) be the property of \(G\) that for any set \(S\subseteq V\) of size at most \(o(n)\) \(S\) is \(4\)-list-colorable.

Lemma. \(G\) has property \(D\) with probability \(1-o(1)\).

Proof. [TODO: no clue how to do it but feels true]

Lemma. In the planted model, conditional on property \(D\) we are quite likely to have property \(E\).

Proof. We give an algorithm for finding a nearby solution. Throughout the algorithm vertices will be either asleep, awake, or dead. Start with all vertices asleep. Let \(v_0\) be the vertex we want to change the color of and let \(V_1,\ldots, V_k\) be the color classes. Let \(V_\ell\) be the target color that we want to switch \(v_0\) to be. To start we kill vertex \(v_0\). If \(v_0\) has no neighbors in \(V_\ell\) then it is trivial. Otherwise we wake up \(v_0\)’s neighbors in \(V_{\ell}\). While there are awake vertices remaining we then repeat the following process:

- Pick a random awake vertex \(w\) and kill it.

- If there are at least \(5\) color classes that \(w\) has no edges to, then we do nothing more.

- Else, choose \(5\) color classes randomly and wake up all of \(w\)’s neighbors in these color classes.

It turns out that this is a subcritical branching process. So the number of dead vertices is at most \(o(n)\).

Now we describe how to color vertices. If a vertex is still asleep at the end we assign it its original color. For the dead vertices besides \(v_0\) we give them each a list of at least \(4\) colors, namely the \(5\) sets that they had no neighbors in if applicable, or the \(5\) sets that they woke up, except we don’t let them choose \(V_\ell\).

Then we use the \(4\)-list-colorable property to get a coloring for the induced subgraph on dead vertices. Finally we give vertex \(v_0\) the color \(\ell\).

We claim that this is a proper coloring. Edges between dead vertices are ok by assumption that the subgraph was list-colorable so we could chose a coloring. Edges between asleep vertices are ok because they were ok to start with and we didn’t change them. Edges between asleep and dead vertices are ok because if there is an edge between asleep vertex \(u\) and dead vertex \(w\) then \(w\) did not get labelled with the color of \(u\) or \(u\) would have been woken up.

Rigid variables above the algorithm threshold

Theorem. There is a big subgraph \(G_*\) of \(G\) with the property that every vertex has a lot of neighbors of each other color.

Lemma. solve planted version

Lemma. bound on expansion

Corollary. It’s pretty easy to show from the theorem that no vertex in \(G_*\) can have a close coloring.

shattering

Now we will prove shattering. They want some notion of distance that plays nicely with permuting colors, not exactly sure why but whatever.

Define \(M_{\sigma,\tau}^{ij} = \frac{1}{n} |\sigma^{-1}(i)\cap \tau^{-1}(j)|\). Our notion of distance between \(\sigma, \tau\) is now gonna be frobenius norm of \(M_{\sigma, \tau}\). Checking for \(\sigma = \tau\) it is much bigger than if \(\sigma,\tau\) are “uncorrelated”.

Theorem. shattering. more specifically,

there are zero solutions at medium distance from \(\sigma\). There are not so many solutions which are pretty close to \(\sigma\).

It is clear how this allows us to define regions.

ok so to prove the theorem

step 1: transfer principle ofc.

Lemma. step 2: prove in planted model.

Proof. I think we just compute expectations.

gg