Shatar: yo parallel computing is amazing. Whenever you have a hard problem just throw more cores at it and that will solve it! You gotta check out these parallel algorithms dude!

JJ: Contrary! I predict that some tasks are intrinsically serial.

Shatar: like what?

JJ: Consider the problem of graph reachability in a directed graph.

Shatar: ah, good connection to todays topic. I hope we will be able to reach a conclusion to the problem.

JJ: I wish you the best of luck with that endeavor, and will be interested to watch you try.

Shatar: As I always like to say “if a problem is really hard, but some relaxation or restriction of the problem is easier, then just pretend like that’s the problem you wanted to solve all along :)”

JJ: Your words contain much wisdom.

Shatar: So yeah anyways, here’s the problem: try to travel between two vertices in a graph. Can you do it?

JJ: Formally, the problem is defined as followsDefinition. Let \(G\) be a directed graph, with vertices \(s,t\in V\) identified. Create an efficient parallel algorithm in the EREW PRAM model of computation to determine if there exists a path \(s\to t\) in the graph.

Shatar: yeah whatever. Ok so in serial this is really easy, any traversal algorithm (DFS, BFS) should work in linear time.

Shatar: so if we wanted to do this in parallel. Well one way to go would be exponentiating the adjacency matrix for the graph. Recall that we can square adjacency matrix in time \(\Theta(\lg n)\) time with \(\mathop{\mathrm{\text{poly}}}(n)\) processors via the straightforward divide into submatrices, recursively multiply those, then add stuff technique. Using exponentiation by squaring we achieve run time \(\lg^2 n\) total for computing the new adjacency matrix. Then we can ready off \((A^n)_{s,t}\) to determine the connectivity.

JJ: In fact, this technique has determined all the connection data. This could be good: it means we have a very efficient transitive closure algorithm. But \(\log^2 n\) span for connectivity of \(2\) vertices seems somewhat wasteful.

Shatar: well. that’s the best one I know. But I can show you a better one for undirected graphs! It works like this:

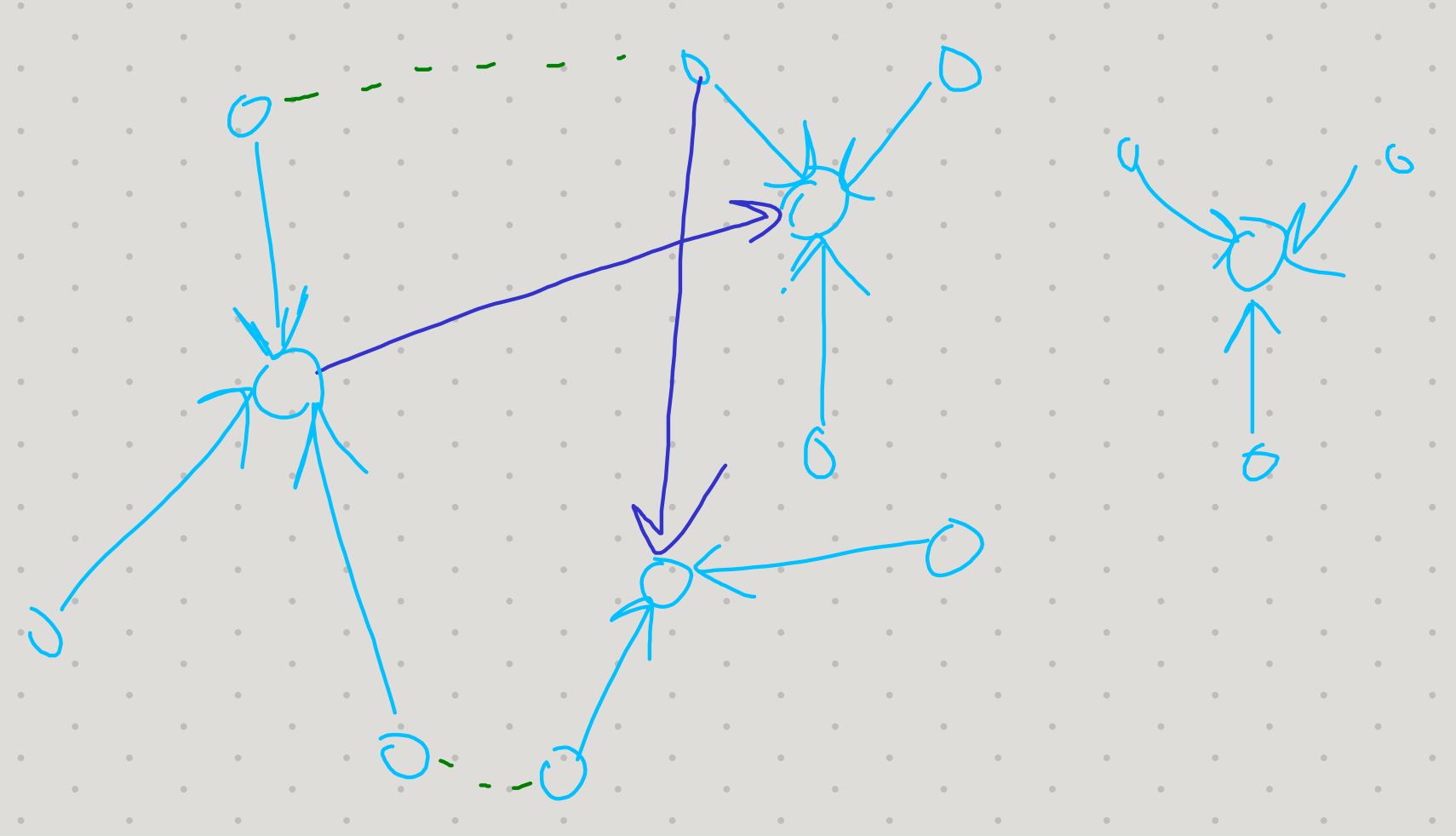

Vertices are grouped into “stars” with a root and a bunch of nodes attached to it. Then, we repeatedly “hook” together stars that have edges between them.

We say an edge is live if it connects vertices belonging to two different stars. In a hook opperation we add a pointer from the smaller index star to the larger index star, symbolizing that they need to be combined.

Hooks turn the stars into a forest of trees. But then we can revert to having stars via pointer jumping, which can be done in parallel pretty well.

JJ: As is, this is still \(\lg^2 n\) span.

Shatar: Ah! But there is a way we can do better. I’ll just give you the rough idea.

we don’t need to have separate steps for pointer jumping and hooking: that was too inefficient.

Now: At any point we will have some stars and some trees. Each round we hook every star to another star / tree. Either we hook to the root of the star or maybe hooks to something else. After each hook we do \(1\) round of pointer jumping.

We can analyze this with the following potential function: $= $ # of live stars $ + $ heights of live trees.

When we hook the stars we decrease number of live stars, which offsets the increase in tree heights resulting in no net potential change. On the other hand, when we pointer jump we halve all of the live tree heights.

Since the potential starts at \(n\) this algorithm takes \(\lg n\) steps. Which is clearly optimal span.

JJ: As described here, it’s still not wrok efficient. But it turns out that you can get within an inverse ackerman function of work optimal. Or just get expected work optimal in the realm of randomized algorithms.

Shatar: so. you convinced? JJ: You had me hooked by the potential function.

Shatar: You’re a star.

Blobby: why are the puns so bad you have to bold them?

Shatar: Go away Blob!