tl;dr

Seems like the most useful types of matroids are partition matroids and graphical matroids. Basically, whenever you have a problem that has some “cycles / forests are important” vibes, maybe time to try matroids. Defining isets to be something like “being incident to some specific vertices” seems like it works sometimes.

LA = linear algebra GT = graph theory

Matroid theory = LA + GT.

basic definitions for matroids

Definition. A matroid is a set of “edges” \(U\) and “independent sets” \(F\subset\mathcal{P}(U)\) (not in the graph theory sense in the LA sense) which I shall call isets with the following properties:

- empty set is an iset.

- subset of an iset is an iset. (hereditary property)

- If you have two isets with distinct sizes, then there is an element of the larger iset that you can add to the smaller iset and still get an iset. (exchange property)

Basis: inclusion-wise maximal set of edges forming an iset Circuit: inclusion-wise minimal set of edges forming not forming an iset. Rank: size of bases.

Example. Uniform matroid: Fix \(r\). Every set of size at most \(r\) is an iset.

Partition matroid: a disjoint sum of uniform matroids

Example. edges = set of vectors. isets = linearly independent sets of vectors

this is a matroid.

Definition. Representation:

Some way of associating a matrix with a matroid.

vandermonde matrix = rep of uniform matroid

Example. graphical matroids

matroid edges: edges in the graph isets: acyclic subgraphs.

It’s not obvious that this is a matroid. Hereditary property is obvious but not exchange. I thought the proof was kind of clever. The proof is as follows.

Let \(A,B \subseteq E(G)\) be isets with \(|A|< |B|\). Here’s how to run an exchange. \(B\) can’t have more edges than \(A\) in any of the connected components of \(A\). Hence \(B\) has an edge going between two connected components of \(A\). This is a safe edge to exchange.

Example. representation of graphical matroids:

you direct the edges arbitrarily and then make a \(V\times E\) matrix with a \(\pm 1\) in entry \(v,e\) if \(e\) goes into / out of \(v\).

edit:

ok so it seems that the matrix representation needs to bring into correspondence isets and linearly indepdent combinations of vectors.

Like in the matrix you have a column \(v_e\) for each edge \(e\). And you need the property that for any iset \(A\subset U\) the set \(\{v_e \mid e\in A\}\) is a linearly independent set of vectors.

Note that not all matroids are representable but nice ones are.

Lemma. Graphical Matroids admit a binary matrix representation

Proof.

You direct the edges arbitrarily and then make a \(V\times E\) matrix with a \(\pm 1\) in entry \(v,e\) if \(e\) goes into / out of \(v\).

Claim 1: if you have a subset of edges containing a cycle then that corresponds to a set of linearly dependent vectors. standard thing: walk around the cycle.

Claim 2: If you have a set of edges which doesn’t contain a cycle then the vectors are linearly independent. Assume for contradiction that the vectors were linearly dependent. Take a non-trivial linear combination of them which makes zero. Then look at just the edges that have non-zero weight in this linear combination. One of those edges must be to a leaf node. But then that vertex doesn’t get non-zero weight in the sum, a contradiction.

rmk: generally we can work in F2 where \(+1=-1\) so we just have vertex edge incidence matrix.

Definition. Transversal Matroids

Given a bipartite graph \(U\sqcup B\) define the matroid as follows: universe is \(U\). \(S\subseteq U\) is an iset if there is a matching saturating \(S\).

Again, it’s not obvious why this is a matroid. Apparently you can prove it with “flows”.

some problems are hard on matroids and some are not.

Example.

- minimum / maximum weight basis: greedy algo works (b/c of exchange principle)

- maximum circuit: NP-hard (HAM is a special case)

- minimum circuit: “even set”: given a collection of subsets \(X_i\) of a universe, find the smallest number of items \(S\) you can take so that \(|S\cap X_i|\) is even for all \(i\) NP-hard

Apparently there are a bunch of hard open problems about whether certain matroid computations can be done in FPT. They mention some stuff that is known to be W1-hard, and some open stuff.

some algorithsm for matroid problems

\(\ell\)-Matroid intersection problem: Given \(\ell\) matroids over the same universe and a value \(k\), determine whether there is a set \(S\subseteq U\) of size at least \(k\) which is independent in all the given matroids.

Turns out the intersection of two Matroids is not generally a Matroid, or else this would be an easy question.

In fact, 3-Matroid intersection is NP-complete.

2-Matroid intersection is in P.

More generally, Matroid Parity is in P.

FVS

Ok, so here’s an interesting fact:

Theorem. FVS is solvable in poly-time on graphs with max-degree \(3\).

Initially this might seem shocking: lots of problems (e.g., hamiltonicity) are hard in graphs wtih max-degree 3. However, I guess we are going to view the \(3\) as a \(2\) in disguise and then throw matroid parity at it.

Proof. We apply a bunch of reductions / rules.

And get it down to the following form:

Have two independent sets \(A,B\). Each vertex in \(B\) has exactly \(3\) neighbors into \(A\). Your goal is to choose a subset \(S\subseteq A\) of size \(k\) such that \(G-S\) is acyclic (i.e., \(S\) is an FVS).

You make a matroid by considering the graphical matroid of a clique on \(A\).

For each \(u\in B\), with neighbors \(x,y,z\in A\) you associate the pair of “edges” \(P_u = \{xy,yz\}\) (matroid edges not actual edges, \(B\) is an independent set).

For \(X\subseteq B\) define \(Z_X = \bigcup_{u\in X} P_u\). The hope is that \(G[A\sqcup X]\) is acyclic iff \(Z_X\) is an iset in the matroid, and furthermore the pairs in \(Z_X\) are disjoint.

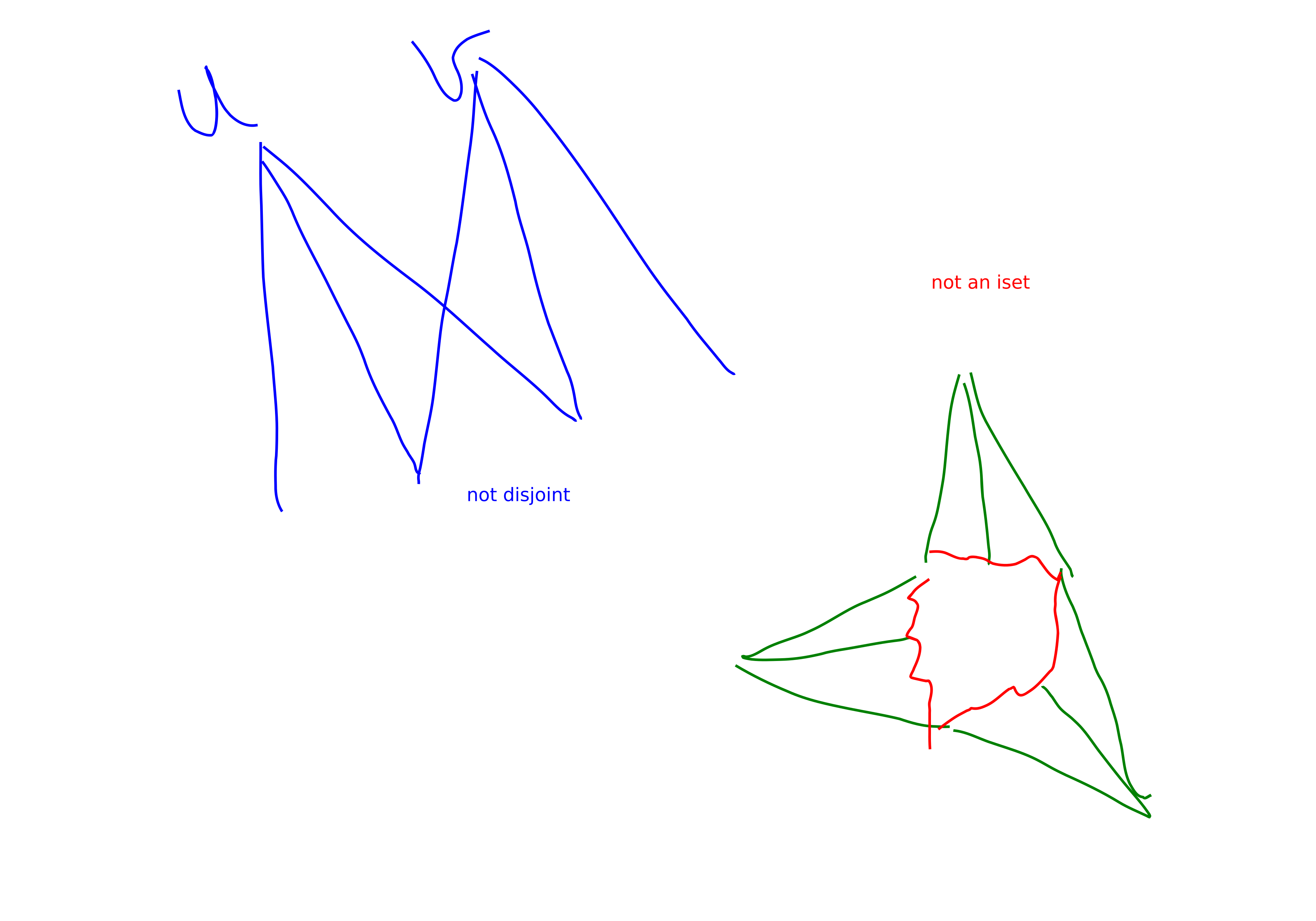

One direction is fairly straightforward. If \(Z_X\) is not an iset we find a cycle in \(G[A\sqcup X]\) easily. If \(Z_X\) has two non-disjoint pairs we also find a cycle in \(G[A\sqcup X]\) easily.

These are depicted below

The other direction is more involved. Assume \(G[A\sqcup X]\) has a cycle. We use it to show that we didn’t solve the matroid parity problem.

Anyways this shows that solving matroid parity lets you solve this problem.

a fun game

For sets \(A,B\) we use the notation \(A\perp B\) to denote \(A\cap B = \varnothing\). For events \(X,Y\) we use the notation \(X\perp Y\) to denote that \(X,Y\) are disjoint events. If we’re lucky, for integers \(x,y\) we will use the notation \(x\perp y\) to denote that \(x,y\) are relatively prime. And maybe for vectors \(x\perp y\) to denote orthogonal vectors. And maybe for vector spaces. Anyways, I am liable to use \(\perp\) to mean literally anything that has the right vibes.

Here’s a fun game:

Alice is dealt a family of \(p\)-element sets \(\mathcal{A}\). Bob is dealt a \(q\)-element set \(B\). Alice knows \(q\) but not \(B\). They sit around in silence. Then bob reveals \(B\). Alice wins if she can reveal \(A\in \mathcal{A}\) with \(A\perp B\). Fun.

Ok, let’s make it slightly more fun: Alice has bad memory but can’t stand losing. She wants to compute a q-representative subset of \(\mathcal{A}\). This set needs to satisfy:

- it’s just as good for the game as \(\mathcal{A}\) (i.e., for any set \(B\) that she could win on before she can still win).

- it’s as small as possible.

Turns out that by a really sweet combinatorial lemma, Alice can find a “small” representative set (modulo your definition of small).

Bolobas’s lemma:

Lemma. Suppose you have \(p\)-element sets \(A_1,\ldots, A_m\) and \(q\)-element sets \(B_1,\ldots, B_m\) with \(A_i\perp B_j\) iff \(i=j\). Then \(m\le \binom{p+q}{p}.\)

Proof. Randomly order the universe. Let \(X\le Y\) denote the event \(x\le y\) for all \(x\in X, y\in Y\) with respect to this ordering. Let \(E_i\) denote the event \(A_i\le B_i\). Observe that \(E_i\perp E_j\) (disjoint events) (draw a picture). Hence, \[m \le 1/\Pr[E_i].\] But clearly \(1/\Pr[E_i] = \binom{p+q}{p}\), so we win.

Ok, now we generalize this “game” to a “game” on matroids.

We say that \(A\) fits \(B\) (wrt some matroid) if \(A\perp B\) and \(A\sqcup B\) is an iset in the matroid.

Now Alice’s goal is when Bob reveals his set to have a set that fits it.

Theorem. Alice can still forget all but \(\binom{p+q}{p}\) of her sets. And we can somehow use MM to compute what she should forget.

applications

Now we use the representative set stuff to get FPT algorithms for some problems.

Proposition. Ed-Hitting Set and \(d\)-hitting set have kernels with universe size at most \(\binom{k+d}{d}\cdot d\) and at most \(\binom{k+d}{d}\) sets.

Proof. Apply the theorem that says we can in poly-time compute the rep set. rep set is a kernel.

some problems

Proposition. transversal matroid is a matroid.

Proof. only hard part is exchange.

flow / augmenting paths?

Proposition. Intersection of Matroids needn’t be a matroid

Proof. Consider the Matroids \(M_L, M_R\) where \(M_L\) is the matroid where a set of edges is an iset if “each vertex in \(L\) touched by at most two of your edges.” \(M_R\) is defined symmetrically.

Then \(M_L\cap M_R\) is not a matroid. Draw a certain cycle and a path, and you can show that you can’t do an exchange.

Proposition. Intersection of uniform matroid with another matroid produces a matroid. Furthermore, if you had a representation of the matroid you are intersecting with you can compute a representation of the matroid obtained by intersecting with the uniform matroid.

Proof. It is obvious that this is a matroid.

However, I think the computing the representation question is cute! Here’s how to do it: Take a random projection of your original matrix down to a matrix of the appropriate size.

Ok, so when does this work? Well, you need your original matrix to be over a field of size \(p\gg r|U|^{r}\) where \(r\) is the rank of the uniform matrix you are intersecting with.

If you think of \(r\) as a constant then this is still just \(O(\log |U|)\) bits to write down: not bad!

Why does this work? Well, we union bound the following expression:

If you take \(r\) vectors which are linearly independent and project them down to \(\mathbb{F}_p^r\) the chance that they are still linearly independent is like \((1-1/p^{r})(1-1/p^{r-1})\cdots (1-1/p)\). Which yay we can union bound.