Work in progress

In this blog post I summarize “Stronger 3-SUM Lower Bounds for Approximate Distance Oracles via Additive Combinatorics” by Abboud Bringmann and Fischer and also discuss the very similar “Removing Additive Structure in 3sum based reductions” by Jin and Xu. I will present the results “backwards”, because I think this makes the motivation clear. In particular, I will present the results in the following order:

- Reduction from “sparse triangle listing” to \(C_4\)-enumeration.

- Reduction from 3SUM instance with \(n^{2+\delta}\) additive energy to sparse triangle listing.

- Reduction from 3SUM instance with \(O(n^{3-\varepsilon})\) additive energy to 3SUM instance with \(n^{2+\delta}\) additive energy.

- Reduction from 3SUM instance with \(\Theta(n^{3})\) additive energy to 3SUM with \(n^{3-\varepsilon}\) additive energy.

Before giving the proofs, it will be helpful to state all the results.

Remark. The 3SUM problem is, given a list of numbers, are there any \(3\) summing to \(0\)? The 3SUM conjecture states that there is no \(n^{2-\varepsilon}\) algorithm for 3SUM.

Theorem. 3SUM is “just as hard” when restricted to sets with additive energy \(n^{2.9999}\).

Theorem. 3SUM is “just as hard” when restricted to sets with \(n^{2.0001}\) additive energy.

Theorem. Fix \(\varepsilon>0, k_{\max}\ge 3\). The sparse triangle listing problem is, given an \(n\)-vertex graph \(G\) where all vertices have degrees in \(\Theta(\sqrt{n})\) and where \(G\) has at most \(O(n^{k/2})\) \(k\)-cycles for each \(k\in [3,k_{\max}]\) list all the triangles. Under the 3SUM conjecture there is no \(O(n^{2-\varepsilon})\)-time algorithm for sparse triangle listing.

Theorem. Assuming the 3SUM conjecture, there is no \(C_4\) enumeration algorithm in time \(\widetilde{O}(n^{2-\varepsilon}+t)\) or \(\widetilde{O}(m^{4/3-\varepsilon}+t)\) where \(t\) is the number of \(C_4\)’s.

4-cycle enumeration

In this section we reduce sparse triangle listing to \(C_4\)-enumeration.

Proof. Assume that we have a \(C_4\) enumeration algorithm with running time \(\widetilde{O}(n^{2-\varepsilon}+t)\) (where \(t\) is the number of \(C_4\)’s).

Randomly partition the vertex set into \(s=n^{\varepsilon/4}\) parts: \(V=V_1\sqcup V_2 \sqcup \cdots \sqcup V_s\). For each tripple \(i,j,k \in [s]^{3}\), we make a graph \(G_{ijk}\). In \(G_{ijk}\) we make 4 copies \(v_1,v_2,v_3,v_4\) of each vertex \(v\in V_i\sqcup V_j \sqcup V_k\). We add the following edges:

- \(\{v_1, w_2\}\) if \(\{v,w\}\in E(G)\)

- \(\{v_2, w_3\}\) if \(\{v,w\}\in E(G)\)

- \(\{v_3, w_4\}\) if \(\{v,w\}\in E(G)\)

- \(\{v_1,v_4\}\)

Claim 1: Each triangle in \(G[V_i\sqcup V_j \sqcup V_k]\) becomes a \(C_4\) in \(G_{ijk}\).

Claim 2: Each \(C_4\) in \(G_{ijk}\) either corresponds to a \(C_4\) in \(G[V_i\sqcup V_j \sqcup V_k]\) or a \(C_3\) in \(G[V_i\sqcup V_j \sqcup V_k]\). And each \(C_4,C_3\) in \(G\) generates \(O(1)\) \(C_4\)’s in \(G_{ijk}\)’s.

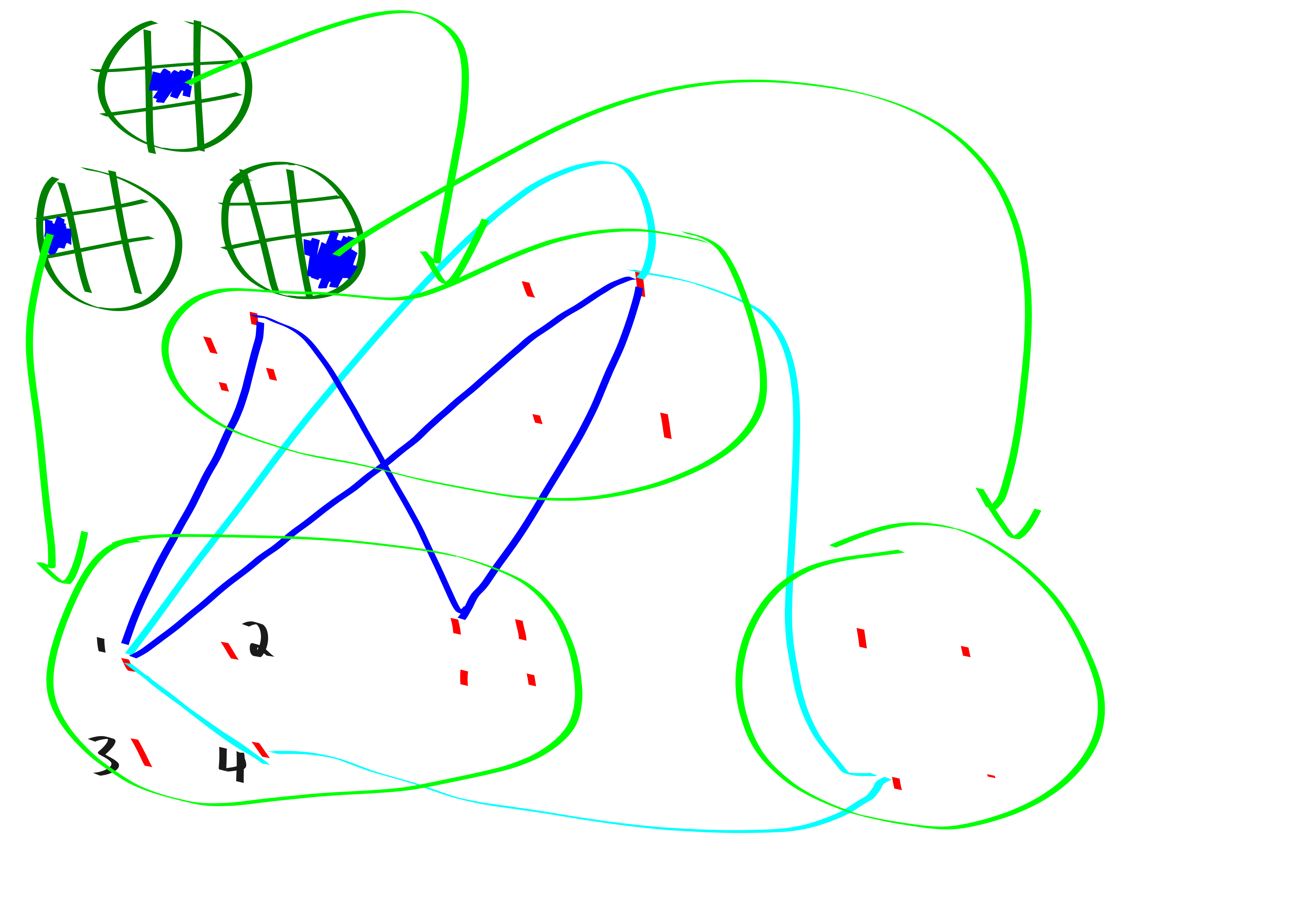

Proof by picture of Claims 1 and 2:

Claim 3: Thus, the number of \(C_4\)’s across all \(G_{ijk}\) is at most \(O(n^{2}/s + n^{3/2})\).

proof: Each \(C_4\) from \(G\) survives the slicing with probability \(1/s^{4}\). Thus, the expected number of survivors is \(ts^{3}/s^{4}\) (where \(t\) is number of \(C_4\)’s). By assumption there are at most \(O(n^{2})\) \(C_4\)’s in \(G\) so this is bounded by \(O(n^{2}/s)\).

The number of triangles in \(G\) is \(O(n^{3/2})\).

Adding these up gives the desired bound.

claim 4: Algo run time is \(O(n^{2-\varepsilon/4})\). The run time is bounded by \[\sum_{ijk\in [s]^{3}} n^{2-\varepsilon}+t_{ijk} \le n^{2-\varepsilon+(3/4)\varepsilon} + n^{2-\varepsilon/4} \le \widetilde{O}(n^{2-\varepsilon/4}).\]

This same computation would show that you’re toasted if you were assuming the existence of an \(m^{4/3-\varepsilon}\) time algorithm instead.

I think the tilde everywhere is because we have given an algo with a certai expected running time, and in order to boost this to working in the desired time whp we can repeate it \(\log n\) times, terminating if its taking longer than twice the expectation.

Remark. Everything would go through identically in the above proof if you replaced “sparse triangle listing” problem with “sparse pentagon listing” problem. Of course, the difference is that I don’t know a proof based on 5sum that “sparse pentagon listing” is hard. Also I’m not sure what to define “sparse pentagon listing” as.

sparse triangle listing

Proof. Let \(G = \mathbb{F}_p^{O(\log n)}\) be the group that all our sets live in. Our 3sum instance is an \(n\)-element set \(A\subset G\), which we may assume by the theorem about decreasing energy has additive energy at most \(O(n^{2.0001})\).

Let \(G'\) be a subgroup of \(G\) with size \(\sqrt{n}\).

Let \(h_1,h_2,h_3: G\to G'\) be random projections.

Construct a tripartite graph as follows:

Vertex set \(X\sqcup Y \sqcup Z\) with \[X = G' \times G' \times \{0\},\] \[Y = G' \times \{0\} \times G',\] \[Z = \{0\} \times G' \times G' .\]

Edge set: For each \(a\in A\), place an edge \(\{x,y\}\in X\times Y\) if \(y=x+h(a)\). etc.

pseudo-solution: \(h(a)+h(b)+h(c)=0\). real solution: \(a+b+c=0\).

claim 1 psuedo-solutions basically correspond to triangles, so triangle listing would suffice to sift through all the pseudo-solutions and find a real solution. More precisely, each pseudo-solution turns into \(O(1)\) triangles and the labels on each triangle correspond to a pseudo-solution.

Here’s why: if you have a triangle, i.e., a closed walk, then its gotta satisfy \(h(a)+h(b)+h(c)=0\) or it isn’t a closed walk.

The reverse side is a bit more subtle but not too bad. I claim that for any \(a,b,c\) with \(h(a)+h(b)+h(c)=0\) it generates at most \(6\) triangles. Basically you gotta satisfy some system of equations. And the only way to do it is

\[x_1=-h_1(a), x_2=-h_2(a)-h_2(b), x_3=-h_3(a)-h_3(b)-h_3(c)=0,\] and then to define \(y\)’s and \(z\)’s based on the \(x\)’s in the obvious manner.

claim 2: Probably not too many triangles. More precisely, there are two cases:

- case 1: there are more than \(n^{3/2}\) real solutions to the 3sum instance. In this case we can guess like \(\sqrt{n}\log n\) \((a,b, -a-b)\) triples and with high probability we will hit a solution.

- case 2: there are at most \(n^{3/2}\) real solutions. Then it remains to count the contribution of fake pseudo-solutions to the triangle count. But observe, \(\Pr[h(a+b+c)=0] = 1/n^{3/2}\) so long as \(a+b+c\neq 0\). Hence, the expected number of fake pseudo-solutions is \(n^{3}/n^{3/2}.\)

Thus, the number of triangles is \(O(n^{3/2})\), as desired.

claim 3: counting cycles

For simplicity we assume \(A \cap -A = \varnothing\), this just simplifies the labelling scheme and is not necessary.

Now we bound the number of \(C_4\)’s. Fix some ordering of the parts as “clockwise”. We classify a \(C_4\) with labels \(\pm a_1,\pm a_2,\pm a_3,\pm a_4\) (The \(\pm\)-ness is determined by the orientation) into two types:

- pseudo-cycle: \(\sum a_i \neq 0\). We will arguge that there cannot be too many of these due to independence.

- zero-cycle: \(\sum a_i = 0\). We can’t use independence here. Fortunately, additive energy gives the bound instead!

claim 3.1: Rate of zero-cycles: Let \(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\) be a set of vectors summing to \(0\), spanning a space of dimension \(s\le 3\). Then probability of a cycle with labels \(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\) containing some specific vertex is at most \(|G'|^{-s}\).

proof: simple inductive argument. either you add a new linearly independent vector in which case you get a new constraint that hits your probability with a \(|G'|^{-1}\), or else you get a linearly dependent vector, in which case it can’t have helped your probability.

claim 3.2: rate of pseudo-cycles: Fix vertex \(v\) and \(a_1,a_2,a_3, a_4 \in \pm A\) with \(\sum a_i \neq 0.\) Then, there is a cycle starting from \(v\) labelled with \(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\) with probability at most \(|G'|^{-s-2}\) where \(s = \dim\langle a_1,\ldots, a_4 \rangle\).

proof: It’s basically the same proof as the previous zero-cycles, except we get a boost in the base case. (it is actually convenient for their induction to consider the probability that \(h(a_0)=0\) and “there is a \(a_1,a_2,\ldots, a_k\) walk starting from \(v\)” and define \(s = \dim (a_0,a_1,\ldots, a_k)\)). (remark: they do all this also banning longer cycles and stuff)

claim 3.3: combining the previous two claims to bound the number of cycles:

First we count the expected number of pseudo-cycles: \[\sum_{a_1,\ldots, a_k\in \pm A \mid a_1+\cdots+a_k\neq 0} \sum_{v\in V} \Pr[\text{cycle containing v labelled } a_1,\cdots,a_k].\] We break the sum up by \(\dim(a_1,\cdots,a_k)\). And then we bound the number of \(s\)-dimensional spaces by \(n^{s}\). Size of \(V\) is \(|G'|^{3-1}\) here. Overall we get: \[O(n^{k}|G'|^{-k}).\]

Now we bound the number of zero-cycles, using our bound on additive energy.

claim 4: degree regularization Observe: The expected degree of each vertex is \(\Theta(\sqrt{n})\): for each \(a\in A\) there is a \(1/\sqrt{n}\) chance that \(h(a)=-x_2\) or whatever. It turns out the variance of the degree is \(O(\sqrt{n})\). Thus, we can do the following algorithm: Kick out high degree and low degree vertices. After not too long everyone has degree that is \(\Theta(\sqrt{n})\).

claim 5: put it all together

TODO: understand this one more!

energy reduction amplification

Remark. The Jin, Xu paper shows how to actually get a Sidon set, i.e., a set with the absolute minimum additive energy. Abboud et al only show how to obtain a set with \(O(n^{2.0001})\) additive energy. The Jin Xu result seems pretty cool, but the results are equaly good for our applications. I think the Abboud one is a bit simpler so I will present theirs.

Proof. HASHING!!!!!

Use some hash functions to subsample your instance. Basically in Abboud et al ’s language this is just some random projection.

Intuitively, slicing up the instance kills additive energy faster than it kills 3sum solutions. So the little boost that we started with is enough that we can win here.

TODO: understand more.

energy reduction initial

Proof.

Claim 1: (tripartite) 3SUM is easy if one of the sets has bounded doubling.

proof: For sake of intuition, think of the set \(A\) as being contained in a small interval \(I\) (In general, \(A\) is contained densely in some “approximate group”).

Partition \(B,C\) into \(B_1,B_2,\ldots,\) and \(C_1,C_2,\ldots\) by covering them with disjoint translates of \(A\).

Call \((i,j)\) relevant if it could possibly be the case that \(A+B_i \cap -C_j \neq \varnothing\) just based on the intervals that are covering the dudes. Observe that \(A+B_i\) is contained in a small interval, so it only intersects \(O(1)\) \(C_j\)’s. Then we do the following:

for relevant i,j:

if Bi and Cj are both small (size smaller than n^{1/3}):

brute force check if there is any b in Bi and c in Cj for

which b+c in -A

else if one of Bi, Cj is large:

Use FFT to compute Bi + Cj. Then check if Bi + Cj has

non-empty intersection with -ARun time:

- light: \(n\cdot n^{2/3}\) (\(n\) many, \(n^{2/3}\) brute cost)

- heavy: \(n\log n\cdot n^{2/3}\) (\(n^{2/3}\) many, \(n\) fourier cost)

- total: \(\widetilde{O}(n^{5/3})\).

TODO: talk about Ruzsa covering lemma, and just generally how you do this

Now that we have claim 1, we give the following algo for the initial energy reduction:

while additive energy > n^{2.999}:

A' = use BSG to peel off a set with bounded doubling

check if A' is useful for any 3SUM solutions using the fast

bounded doubling 3sum algo.

if:

so, return the found solution

else:

Evict A' and keep going

if size is really small:

brute force solveClaim 2: As long as the additive energy is larger than \(n^{2.999}\) we almost certainly can do the peeling off step and its probably fast. So, either the size gets too small in which case we can afford to just brute force and find a solution, or if not then we have reduced to a reasonable 3sum instance just with slightly subcubic additive energy.

TODO: argue more formally that this works.