THE PHILOSOPHY ESSAY IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE PHILOSOPHY OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE PHILOSOPHY.

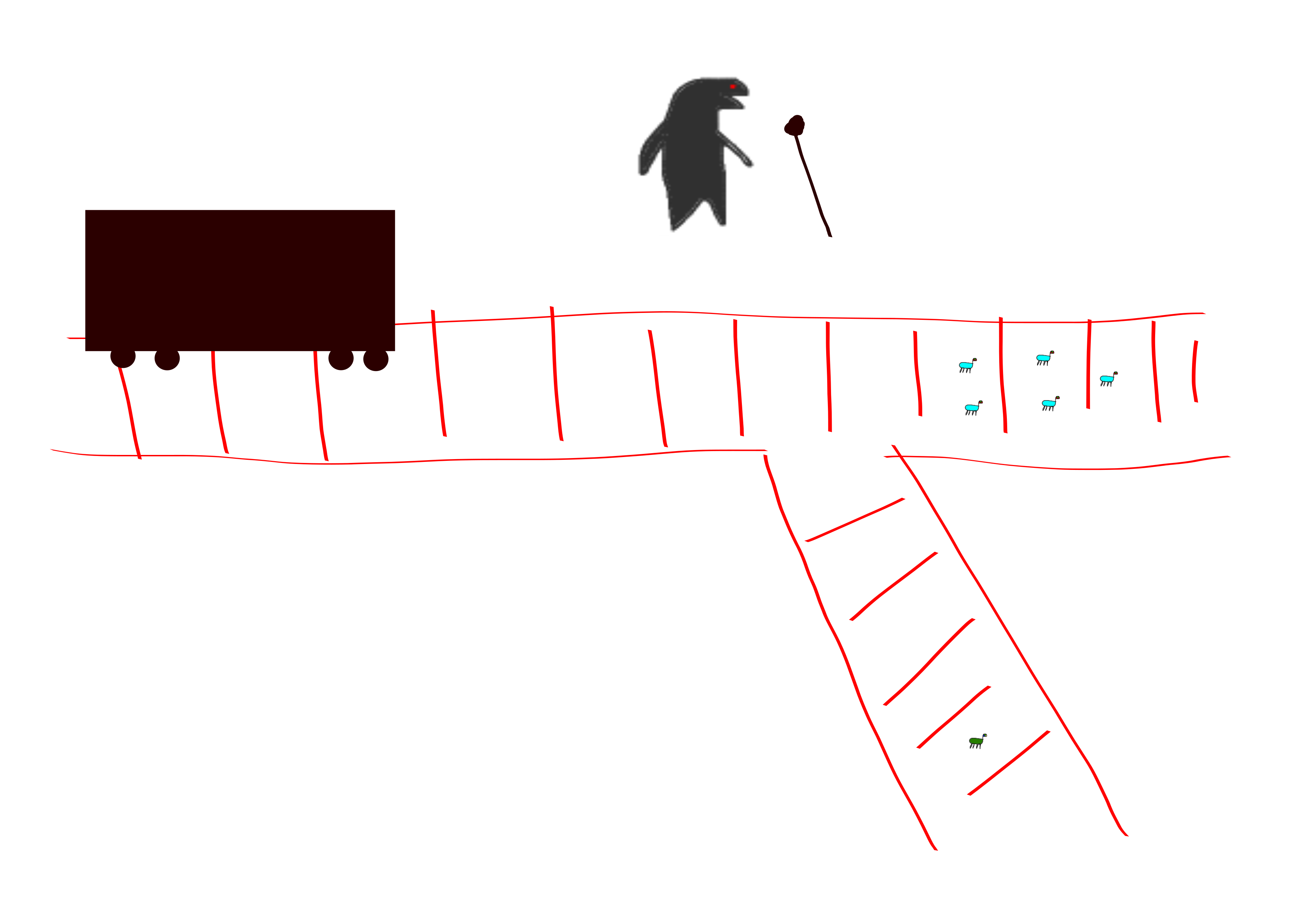

Here are two popular and plausible moral claims: (1) In Thomson’s Bystander case, it’s permissible to pull the lever, redirect the runaway trolley, and kill one person in order to save five; (2) in Foot/Thomson’s Surgery case, it’s not permissible to perform a surgery that kills one person in order to save five. Is there any good way of explaining why it’s permissible to pull the lever but impermissible to do the surgery? (If you think there’s no good way of accommodating both judgments, you should indicate which of the two judgments ought to be given up.)

Introduction

“Bystander” and “Surgery” are two famous moral dilemmas where if the agent refuses to act five people die, and if the agent acts then one person dies. Many people believe that in Surgery it is impermissible to act and cause the death of one to save five, whereas in Bystander is is permissible to act, causing the death of one in order to save five. However, it is notoriously difficult to explain what difference between the two cases permits action in Bystander while prohibiting action in Surgery.

In [1] Foot considers Surgery and several similar moral dilemmas. Foot claims that positive duties – responsibilities to intervene on someone’s behalf – are generally weaker than negative duties – responsibilities to not intervene on someone’s behalf. Foot’s analysis of Surgery is that the surgeon shouldn’t act because acting entails violating a negative right in order to fulfill five positive duties.

In this paper I argue the opposite: it is permissible for the surgeon to kill one to save five. I will start by arguing that negative duties are not actually stronger than positive duties: negative duties merely seem stronger because of implicit confounding factors that render the comparison between the negative duty and corresponding positive duty unfair (i.e., not “all things equal”). After removing these general confounding factors associated with negative duties I will modify several morally irrelevant but psychologically confusing details to clarify why it is right to kill one to save five.

Exegesis

To start I define Surgery and discuss Foot’s analysis of Surgery.

In Surgery Nathan is a highly skilled surgeon with five patients each dying from various organ failures. A healthy individual Anthony walks into the waiting room. Nathan realizes that he could kill Anthony and distribute Anthony’s organs to the five patients to save them.

Should Nathan harvest Anthony’s organs to save five patients?

Many people, including Foot, believe that it is morally impermissible for Nathan to harvest Anthony’s organs. Foot supports her intuition by discussing the distinction between positive and negative duties.

A positive duty (PD) is an obligation to interfere in a situation for someone’s benefit.

A negative duty (ND) is an obligation to not interfere in a situation to someone’s detriment.

For example, if we see a child drowning in a pond we have a PD to save them. If we see a child standing next to a pond we have a ND to refrain from shoving them into the pond.

Roughly speaking Foot believes that, ceteris paribus, NDs are more than five times stronger than PDs. More formally, I think Foot would support the following “PDND Principle”:

Consider two cases:

(1) If Claire performs interference \(\phi_1\) in case 1 it will prevent bad event \(E\) from befalling five (or fewer) agents.

(2) If Claire performs interference \(\phi_2\) in case 2 then a bad event \(E'\), similar to case 1’s bad event \(E\), will happen to a single agent.

The PDND Principle states that Claire’s PD to \(\phi_1\) in case 1 is less compelling than her ND to refrain from \(\phi_2\)ing in case 2. In other words, if forced to choose either to do both \(\phi_1,\phi_2\) or to do neither of \(\phi_1,\phi_2\), the morally correct decision is to do neither of \(\phi_1,\phi_2\).

Now I describe how I think Foot would use this principle to explain the difference between the aforementioned cases concerning a child and a pond. The bad event in both cases is the child’s death, and the affected agent is the same in both cases. Pushing a child into the pond is worse than neglecting to save a drowning child, because Claire has a ND to not harm the child and merely a PD to save the child.

The PDND Principle crucially requires comparing similarly-bad events in cases 1 and 2. To see why, consider the following case:

Claire notices a child drowning in a pool. For some strange reason people are arrayed around the pool in a temporary drug-induced sleep. In particular, in order to go into the pool and save the child Claire must step on someone causing them mild injury.

Of course Claire has a ND to refrain from harming these people. But it is clearly overwhelmed by the PD to save the drowning child. Thus, it does not make sense to apply the PDND Principle in cases where the bad events differ.

Foot explains Surgery as follows:

Nathan has a PD to save the five patients, but a ND to not kill Anthony. Nathan’s ND is stronger than his PD, so he shouldn’t kill Anthony.

Foot does not consider Bystander, but it is instructive to apply her analysis to Bystander. Recall the case:

In Bystander Nathan stands next to a lever controlling the path of an out-of-control train. If Nathan does nothing, five people on the track ahead will die. If Nathan pulls the lever the train will be diverted to kill Anthony, who is on the other track.

Should Nathan pull the lever?

Just like in Surgery, Nathan in Bystander has a PD to save the five people the train is headed towards, and a ND to not kill Anthony by directing a train to run over him. Then, assuming the PDND Principle we conclude that Nathan must refrain from pulling the lever. This conclusion seems rather unintuitive: most people feel that the decision to pull the lever is obvious. I think this intuition is exactly right, and that in Surgery it is also right to kill one to save five.

In the next section I will argue that the PD/ND distinction is illusory and only appears plausible because of traits implicitly associated with NDs. Then I will modify morally irrelevant details of Surgery to promote correct moral intuition about the case.

Analysis

Specifying Morally Relevant Details

A crucial assumption in the PDND Principle is that we compare comparably-bad events. I now present four common implicit differences between events that we have a ND not to cause and events that we have a PD to prevent. Once these are explicitly removed I believe the distinction between PDs and NDs evaporates.

I. Uncertainty

A large difference between events we should not cause and events we should prevent is uncertainty about the future. For instance, consider the difference between the following two cases:

- Alice poisons her cat.

- Alice neglects to feed her cat.

Intuitively, (1) is morally worse than (2). But are the caused and not-prevented events in question really the same? Notice that in (2) Alice’s neglect might lead to her cat’s death. But the cat might also find other food; its death is not certain. In contrast, in (1) it is nearly certain that the poison will kill the cat. Removing the element of uncertainty seems to eliminate the difference between (1) and (2): poison and starvation are merely two different tools to the same end.

With regards to Surgeon, we may be implicitly biased to believe that the Surgeon can’t be certain or even confident in succeeding in such a difficult operation. Indeed, if Nathan were very uncertain that he could successfully perform the organ transplants leading to the five patient’s full recoveries then it would clearly be wrong for him to kill Anthony. However, the assumption in Surgery is that this uncertainty does not exist: Nathan is a perfect surgeon and knows he could successfully perform the procedure.

II. Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The issue of uncertainty is closely related to the issue of self-fulfilling prophecies. One of the characteristics of Surgeon which makes Surgeon feel unrealistic is the dichotomy: the only options available to Nathan are killing Anthony or letting the five patient’s die. If Nathan accepts this dichotomy and focuses all his energy on killing Anthony then he may fail to notice alternative solutions. My point is not that one should always procrastinate important decisions: the price of delaying might be quite large. Rather, my point is that it is bad to prematurely resign oneself to a dichotomy between two actions.

To remove this from the calculation we can imagine that in Surgery the patient’s have very short amount of time left to live and Nathan, as an experienced surgeon, is quite confident that no alternative solution will be manifest. We may even go as far as to assume that Anthony is a relatively rare individual in that he happens to have organs that would be compatible with all of the dying patients. Thus, all alternative courses of action are ruled out.

III. Side-Effects

A third reason why negative duties are often more pressing than positive duties is that even well-intentioned actions can have adverse unintended side-effects. This is also related to the issue of uncertainty because it is very challenging to predict what these side-effects will be.

For a simple example, imagine Nathan really did kill Anthony, and people found out. This could plausibly cause some degree of loss of trust in hospitals, which could lead to people avoiding hospitals resulting in injuries or even death. To mitigate this possibility in Surgeon we stipulate that there will be no side-effects. In particular, no one will ever learn what Nathan did.

One other important side-effect to consider is the effect of the action on Nathan. For instance, imagine that Nathan’s psychology was such that if he actively killed Anthony he would later commit suicide, or that he would become a serial killer. If Nathan killing Anthony could have drastic side-effects such as these then it seems much more likely that killing Anthony would be wrong. Thus, an assumption in my definition of Surgery is that there are no such extreme side-effects due to Nathan’s psychology.

IV. Blame

A fourth factor that can confuse our sense of responsibility is blame. For instance, it could plausibly make a moral difference to the case if the patient’s had somehow brought their maladies upon themselves, e.g., by taking some drug or not caring for their health appropriately. The simplest way to resolve this concern is to slightly augment the case to make it clear that the patients do not deserve their sickness. For instance, we can imagine that the patients were poisoned by an insane murderer, resulting in their organ failures.

Modifying Morally Irrelevant Details

Thus far I have specified four morally relevant details in Surgery that are necessary for the morality of the case to not be ambiguous. Now I will modify several morally irrelevant details of the case to help clarify what the right action should be.

I. Gruesome

Surgery is overly gruesome. We have already disallowed the gruesome nature of the surgery from having extreme side-effects on Nathan’s psychology, so we are free to modify the case to be less gruesome. At the same time, we can remove the condition that Nathan is a surgeon. We might be more inclined to think that a surgeon has special responsibilities not to harm their patients compared with a person without this role. However, as I am framing the case the details of Nathan’s occupation should not be important. Thus, we could create the following analogous case:

Anthony and five others are scuba-diving deep under water. Suddenly the oxygen supplies of the five other divers fail. Nathan has a button he could press which would redirect Anthony’s oxygen supply to the other five divers, saving the five but killing Anthony.

Should Nathan press the button?

II. Property

A confusing factor in both the scuba-diving case and Surgery is that Anthony’s oxygen supply and Anthony’s organs are his property. Thus, we are not only killing Anthony but also stealing from him. However, this is not particularly morally relevant because failure to prevent death is much worse than stealing. For instance, consider the following case:

Nathan could save the life of one patient by stealing Anthony’s kidney. Afterwards Anthony would never discover the lost kidney and would lead a normal life.

Is it permissible for Nathan to take Anthony’s kidney to save a patient?

This case may also suffer from being overly gruesome. As a cleaner case, imagine that Nathan could somehow by stealing Anthony’s watch (while Anthony is sedated, such that Anthony never finds out) save a patient’s life. I think both of these cases indicate that Nathan’s PD to prevent death is stronger than his ND to refrain from stealing.

III. How many PDs is one ND?

Another reason to question the judgment based on weighing the number of PDs versus the number of NDs involved is the arbitrariness of where we draw the cut-off between how many PDs are equivalent to one ND. For instance, imagine Nathan’s choice was whether to kill Anthony in order to save one-million people. It seems clear that he must kill Anthony. Decreasing the number one-million, we find that an advocate of not killing Anthony in Surgery must define some arbitrary cut-off \(x\ge 5\) for when killing one person to save \(x\) people becomes impermissible. But there seems to be little reason why this should be larger than \(5\).

I hope these morally irrelevant modifications of Surgery persuade the reader that the correct course of action in Surgery is to kill Kevin.

Conclusion

I have demonstrated that the supposed difference between the moral importance of PDs and NDs is illusory. By fully specifying Surgery and modifying morally-irrelevant details, I have shown that it is permissible for Nathan to harvest Kevin’s organs, killing one to save five.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nathan for provoking me to think more deeply about this question and give an uncomfortable answer. I also would like to thank Julian for helping me better articulate my argument and for suggesting morally irrelevant details that I could remove from the Surgeon case to make the conclusion more intuitive.

Bibliography

[1] Foot, Philippa. “The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect.” (1967).